An Interview with Johnny Sansone

This interview done by Mark Goodman in 2012. With Johnny coming to town for a show at Cottonmouth Southern Soul Kitchen on January 15 within are unique insights into Johnny.

Tickets are available at Suncoast Blues Society Shop

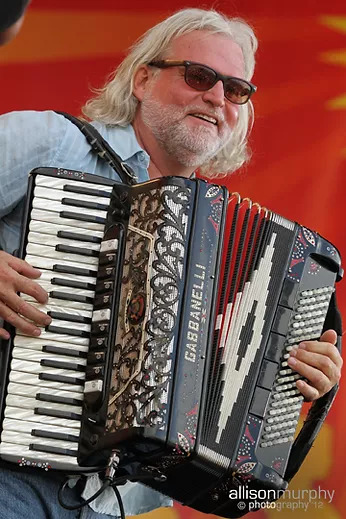

To many people on the blues scene, Johnny Sansone is a relatively new name. It was his last two records; Poor Man’s Paradise & The Lord is Waiting that really seemed to catch fans attention and bring him the recognition he so richly deserves. Sansone’s songwriting provides a window into his world, the city of New Orleans and yes, into his very soul. Best known for his harmonica and accordion skills, Sansone is also an accomplished guitarist. I had the opportunity to see his one-man show when he opened for RSB in Pennsylvania. I have lost count of the times I have seen him perform, but he always seems to pull something new out of his toolbox that keeps me amazed.

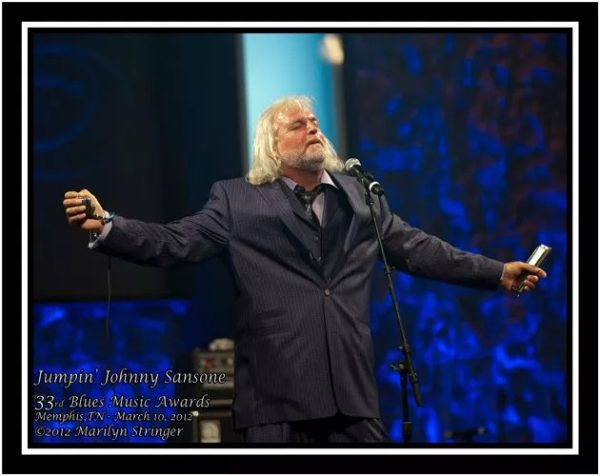

With his win for Song of the Year at the 2012 Blues Music Awards, maybe the spotlight will shine a little brighter on this multi-talented artist.

MG: Tell me a bit about your early days. Where you’re from originally and how you got interested in music.

JJS: Early days… my father was a sax player in big bands. He played with Dave Brubeck during World War II, and he got me started playing saxophone when I was a teenager living in New Jersey, just outside New York City. He got me interested early and he had a pretty cool record collection. A lot of Duke Ellington and Count Basie, stuff like that.

I started playing saxophone at eight years old and then I picked up the harmonica and guitar just a few years later and started collecting my own records.

MG: Okay. Why did you switch from saxophone to harmonica?

JJS: Well, I was taking lessons and I was just a little kid, and the saxophone was bigger than I was, you know. The harmonica was a lot easier to carry around. But I played saxophone up until it was stolen in the early 80’s in Kansas City. It was my dad’s horn, and after it was liberated from my van, I never played saxophone again.

MG: Okay. Tell me a little about your early professional career.

JJS: I started doing gigs when I was in high school. You know, we had a little blues band and I always played Jimmy Reed kinda stuff with the harp in a rack. When I went to college at Colorado State, I met a piano player who was from Kansas City and a guitar player from Chicago. We all had the same kind of record collections, so we put a band together and started playing parties. That eventually gave way to playing in the bars and clubs.

It was a really good time back then for blues. It was the late seventies, and I was still a teenager then. A lot of the Chicago acts were coming through on their way to California. So, you know I got to meet and hang out, and learn from these guys. Cotton was coming through and Jimmy Wells, most of my favorite harmonica players, so I got to be friends with them and study them. It was just a really good time back then when a lot of real deal blues guys were walking the earth. (Chuckling) It’s a lot different today.

MG: Okay. How did you eventually get your gig with Ronny Earl?

JJS: Well, we skipped through a couple years there, but I had gone to the east coast to join a band with Jimmy Carpenter called the Alcho-Phonics. This would’ve been around ’84, something like that. We both ended up quitting that band and putting together…actually reassembling the band that I had that included members of the Iguanas, and moved to Richmond, Virginia where Ronnie is from, and we were putting together our first record.

Now I’d known Ronny since he was playing with Room Full of Blues. They would come through Colorado and hang out after shows at my house. Years later I asked if he would do a guest spot on the first record that came out on King Snake Records. The band didn’t last much longer after that, about another six months to a year.

We had done a couple of shows in support of Ronnie and he had heard my band was breaking up, so he eventually just gave me call. He said, “I need a singer and harp player. Would you come up to Boston?’ So, it all fell into place and I moved up there around the late 80’s.

MG: What made you decide to make the move to New Orleans?

JJS: I had been coming to New Orleans for years. I lived in Austin for about a year and spent most of my time driving down to New Orleans and staying with friends.

I had family here and my cousin owned an oyster bar and, you know, it’s a really great place to visit but I was on the road all the time. So, after I left Ronnie’s band, the Iguanas were here and most of my old buddies from Colorado had moved down here. Actually, they became the Iguanas about the same time I moved down here. We were gonna all get together and play but it didn’t work with what I was doing. I had my CD coming out on Ichibon Records, so when I got to town, I was trying to promote that record and I kinda just moved all my stuff here. Things were better then because I was touring a lot and had a house Up-Town.

MG: What is it, in your opinion, that gives New Orleans’ music its distinctive vibe?

JJS: Yeah, I mean… it’s a really tough question and there is no definitive answer. I mean, in my opinion, I think it’s the syncopation of the city… it seems to have a lot of grease on it, it seems slippery, and the tempos are relaxed. It’s almost like an intoxicating sound like the drummers and the second-line beats. I’ll give you an example: I was playing in Lucerne, Switzerland and my drummer was warming up doing some second-line thing during sound check. This guy came over to me and said, “Man, I’m sorry, I know this is a big show.” I asked him what he was sorry about and he said, “Your drummer, he’s drunk.” I said, “He’s not drunk, he’s not even drinking.” He said, “It sounds like he’s drunk.” (Laughing) I told him that’s the style of the way he plays. These guys didn’t really get the idea that the dragging syncopation of the second line is a style. I guess they heard it as a guy that was drunk.

Sometimes people hear this music, and they think it’s… like sloppy. The slop is what makes the music cool, and that’s only a little tiny bit of what I think makes the music here interesting. There are a million different reasons why it’s different from a lot of other music.

MG: Most people are familiar with you as a musician, but most don’t realize what a good songwriter you are. Tell me about your process.

JJS: Well, unfortunately I have… or fortunately, it depends on how you look at it, I’ve been writing from life experiences. I guess the song that was nominated first was Poor Man’s Paradise. It was a tragedy song that I wrote by just gathering people’s pain. I thought it would really be helpful to regurgitate the suffering and that would be a healing process for people.

I had written songs for when the oil spill happened. I heard there was going to be a bunch of records, so I wrote songs for that. It looked like they had cleaned everything up, (laughing) but they haven’t! They haven’t cleaned everything up but the benefits kind of disappeared. It’s a tragic song that I had written and when I played it for people, I saw real emotion. I mean I saw some people crying, you know, I actually saw tears when I played the song. I thought well, all I’m really doing is expressing stories I’d heard and put to music.

MG: You’re a solid songwriter with a fairly long career. Why only four album releases?

JJS: It took a long time to cleanup my Rounder releases and Poor Man’s Paradise. It was kind of a contractual thing. I had written a lot of songs, but I was still under contract with Rounder. I still have a whole lot of songs; I mean I never stopped writing. I guess it was just a timing thing.

MG: This next one is more of a personal question. One of my favorite songs by you is Crescent City Moon, yet I have never heard you do it live. Why is that?

JJS: I actually do that song a lot in my club shows where I always feature a guitar in the song. I think you’ve probably been to a lot of the festival sets and that song is a slow blues and you can only do so many slow blues in a 60–90-minute festival show. For festivals I concentrate more on the harmonica, but I do that song pretty much every night in my club shows.

MG: Being a true bluesman, what made you decide to pick up the accordion?

I saw Clifton Chenier a bunch of times and was really moved by the energy of the music. I was playing guitar at the time and was looking for an instrument that had more voice than the harmonica that I could use as a second instrument. I went to Clifton’s wake and decided the king was gone and I was really fascinated with the instrument, so I started that day. I don’t remember exactly, but it was back in the mid-eighties.

MG: You have a very talented group of friends to play with such as Anders Osborne, Tab Benoit, and Mike Zito to name a few. What’s it like, and what impact does it have on your own music?

JJS: Well, first off, I have to comment on how lucky I am to be in a group with those guys. I owe a lot to Rueben Williams for putting this thing together, making sure that we all came together as The Voice of the Wetlands All-Stars. I went to the session, and I got thrown right in and was standing next to Dr. John and playing accordion. I played on the record but didn’t know I was going to be asked to join the band.

An interesting little story there was, Rueben (Williams) had asked me to come to the session, but I didn’t know what we were going to do. I walked in and they were all there, and guys with a camera.

MG: Believe it or not, I was the guy with the camera if we’re talking about the same session. Anyway, go on.

I took the accordion out but didn’t know what key or what was happening, we just started playing. George Porter was guiding us through the song and giving us the chord changes. I was standing right next to Dr. John, and when it was time for me to take a solo, I was a little bit nervous. Anyway, after my solo I glanced down at Mac (Dr. John). He stopped playing for a second and gave me a thumbs-up. I said to myself, “I guess I must be doing it right.” It was great!

I can’t tell you how important it is to play with a rhythm section like that and being out on the road and seeing what their like. You can’t imagine the importance that goes along with being on stage and playing with what are essentially your heroes at this point. I mean, I don’t even know where to start saying how important it is. Every night something is different, there’s such great imagination in these guys. Everybody is at the top of their game; they’re just an incredible group of musicians.

I’ve known Tab pretty much since he started on the blues scene in New Orleans. I’ll give you a quick little story about how we met. My record had just come out on King Snake Records and Kenny Neal was working down there (Sanford, Fl), and had this Dodge Transvan. It was kinda like a motor home thing and driving around in it was really cool. So, when I saw one for sale I bought it, just because Kenny had one. I did a couple tours then decided to sell it downtown. This kid comes to look at it and I asked him what he wanted it for. He said, “I’m gonna be touring with my band.” I told him that’s what I had used it for and asked what kind of music did he play? He said, “I play blues!” I told him I did too and asked where he was playing. He said he was playing a little bit here and there, so I invited him to sit in with us at the Howlin Wolf. That’s how we met, and he would play with us all the time before he actually had anything going on. He’s been a huge help to me by letting me sit in over the years and putting me on his records. Tab Benoit is a really helpful guy to have in the music world!

MG: In 2008 I was traveling with Tab Benoit for a story, and he played at the Democratic National Convention Party. You were there with the Voice of the Wetlands All-Stars. What was that like?

JJS: Actually, we did the Democratic and Republican Conventions. That was an incredible show and an eye-opening event to take part in, especially the Democratic show. I mean… the people that they had made for an incredible lineup. One of the most beautiful things that I got to do was perform Louisiana with Randy Newman. We had Johnny Vidocovich on the drums, George Porter, Jr. on bass and Anders Osborne on guitar. Waylon Thibodeaux was on fiddle, and I played accordion. We got to do that song at the Democratic National Convention; it was special.

We had gone there as a delegation to make our presence known, to explain what we were trying to do. I don’t know how they made that happen. The guys that worked to put everybody’s schedules together and put us all out on the road at the same time were absolutely amazing. I can’t imagine all the work that went into making it happen. And to be out there with all those guys, I mean, it must’ve been like traveling with the Johnny Otis Show. Oh yeah, and guys standing there with assault rifles pointed right at you when we arrived in Tab’s bus.

MG: Your latest release, The Lord Is Waiting And The Devil Is Too, is full of anguish and anger. Tell me about it.

JJS: Well… I was going through a hard time in my life, so the record is extremely personal. I think what happened was, I had been doing the Tuesday nights at Chickie Wah Wah’s (a club on Canal St. in New Orleans) with Anders Osborne and John Fohl (guitarist for Dr. John). It was kind of a song-writers day, and we would bring fresh songs to play for the first time in front of people. It was always packed with those that wanted us to play a song so they could be the first to hear it.

At the time, I was in a fairly deep blues depression. I was carrying some anger and I was writing like that. Anders was so moved by what he was hearing that he went to Rueben Williams and said we need to record Johnny right now. We’ve got to get in the studio right now. I wasn’t prepared to sing these songs, and especially not prepared to record them. It was Anders and Rueben Williams that essentially dragged me out of my house and into the studio.

As we were recording the songs I said, “Anders, you have to let me know if there’s anything here that I shouldn’t be saying.” I needed someone to listen to the lyrics closely enough because I was pretty wounded and didn’t want to say anything that I would regret later. He said, “All I hear is you expressing your pain and passionately showing your soul.” So that’s how the session went down.

MG: I think it’s a powerful record and apparently the nominators for the Blues Music Awards think so too.

JJS: That completely blindsided me. I was hoping that maybe I would be nominated for player of the year. This was my first all-harmonica record and I thought maybe there’s a chance that I would get nominated for player of the year or something. I thought maybe there’s a possibility, you know. And it’s funny that was the one thing I didn’t get nominated for. I was shocked when I got all those nominations, completely shocked, you know. I didn’t expect that at all.

I owe so much to Anders (Osborne) because he had the vision for the record. I wrote the songs, but it was his idea to go in there with Stanton Moore and those guys. I mean, they essentially did all of the arranging, or almost all of the arranging. And it was Anders’ concept to go without a bass, just drums, guitar, and me. It’s kind of like a Hound Dog Taylor thing, or maybe Black Keys, something like that.

Interestingly, one of the things about this record that I was concerned with, and I don’t know how many people realize this, but Anders didn’t want to put any solos on it. He said, “This is your record. You’re going to play the solos. It’s going to be focused on you. I told him I wasn’t sure people would buy a record that only had harmonica solos. I mean, every song has got harmonica on it. He said, “Trust me! Just play your heart and trust me.” And he was right. I mean, maybe some people were missing guitar solos, and I would’ve loved it if Anders would’ve played some, but this is the way he saw it.

I produced most of my other records, and he co-produced Poor Man’s Paradise, but I had pretty much had the last call on how those records came out. On this one I just handed everything over to Anders. I just put all my trust in him, and he knocked it out of the park for me.

MG: Do you find it easier as a musician to let someone else take the reigns in the studio and just focus on playing?

JJS: That’s not a question I can easily answer. When I went into the studio to do The Lord is Waiting, I was kinda in another world. I wasn’t sure what was happening, and I just set up my stuff and played; I didn’t second guess anything. I just went and did it. I’ve never made a record like that before. I usually have everything worked out, you know, write a song, might make a couple changes, we rehearse everything. This record was done in one day and night. We just went in and played.

Actually, I could see the energy that these guys had. It was like every time a note was played it was with 100 percent passion. There was no, let’s go over the song and see how it sounds. We just went in there and just nailed everything to the wall. It was a session like I’ve never been on before.

MG: I’ve noticed that with that group of musicians in the VOW sessions. They just went in and nailed it on the first take every time.

JJS: When Tab was recording his last record, I went over to Dockside to just hang around and see if I could be any help to those guys. It was incredible to watch. Anders walked in and he played songs that he’d never done, just nailed them. I mean there was no reason to try and do it again. It’s was one take; Bam! I wish people could see how it’s done. You don’t have to look back; you don’t have to do it again. It was really inspiring.

You know, you see bands do twenty-five takes, you know. They just kept doing it over until it was right. But who’s to say what’s right, you know? I think a lot of musicians would agree with me that you can do as many takes as you want, and usually the first couple takes are gonna be the best.

I was in the studio with The Voice of The Wetlands, and we stopped in the middle of a song. Dr. John said, “What’d you stop for?” I don’t remember who it was, but they said there was a glitch or something. Dr. John was like, “man sometimes those glitches are the best part. Just let it roll.”

You always looked for mistakes but sometimes they end up making the cut. You know, you’re playing, and something happens that you don’t expect. It’s not the way you rehearsed it but the passion of the moment.

MG: What’s next?

JJS: Well, I’m at the stage of my career where I’m ready to get out and play. The way I feel today, I would like to play every night until the last night I’m alive. I realize it’s a young man’s game to be out on the road; it’s hard travel. The last ten years or more, I’ve been doing more European tours. They seem to be a lot more doable financially. It’s a whole new game from when I used to tour in the ‘80s. I mean, everything is just so hard. You used to call up a guy and say we’re coming out there, he’d say great, let’s do a show. Now you have to go through eighteen people and send eighteen demos just to get considered.

It’s a different world today and it’s been difficult for me to keep the band together and make enough money to have the kind of players that I want and still be able to get out and tour. It’s too difficult. I think things are gonna get a lot better now, and I’m gonna start being able to get out on the road more. It’s been interesting for me to be in front of people that say, “wow I didn’t know you sang, or didn’t know you played accordion.” They’ve seen me as a sideman playing with Tab or any number of people. They didn’t realize I actually have a career that started long before most of these guys were even out on the road.

It was more lucrative for me to stay in New Orleans, especially before all this Enron bullshit happened. You know, there was a lot of corporate money, and those were great gigs. One corporate party would pay you the same amount you’d make touring blues bars out on the road for a week. You could make your money in a few hours, so it was a smarter thing to do. After they got caught wasting all the investors’ money, they just hired solo jazz players.

MG: It took a long time before you would grant me this interview. Why?

JJS: (Laughing)…You really want me to talk about that?

MG: Well, I was gonna see if you would. They are the competition, you know!

JJS: Well… there was an interview done and…. how do I put this? There was an interview done in another publication where at the end of the interview I said, “I look forward to seeing you when you come down to New Orleans for Jazz Fest. I look forward to seeing everybody. Come and say hello.”

Well, the people that did the interview with listed my phone number at the end of the article. I had people calling me and asking what restaurants to go to, where could we meet for drinks, and could I pick them up at the airport. I don’t know how that happened, but yeah, it’s probably not a good idea to give your phone number out in an interview.

MG: I promise not to do that!

While a lot of New Orleans musicians stay close to home because of the cost to tour, Johnny Sansone has been venturing out more and more. With his membership in The Voice of the Wetlands All-Stars, and guest appearances with The Royal Southern Brotherhood, he has been on the road more and more. His latest release is a powerful look at a tortured soul releasing its pain through music. If you’ve never seen a live performance of The Lord is Waiting, be prepared. You just might catch a little glimpse of that Devil!